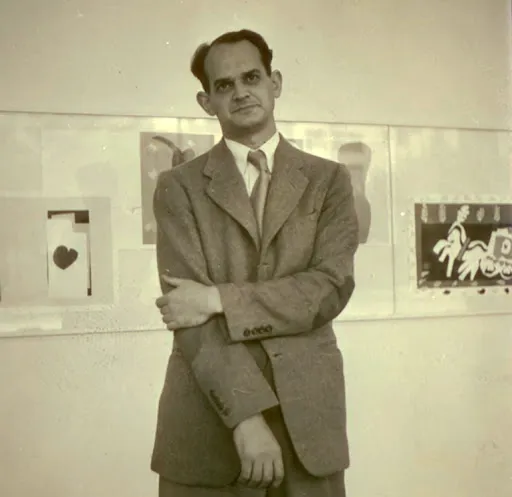

I’ve lately become obsessed with the work of Manny Farber. I had never heard of him until recently. I encountered him in a random movie I watched, which itself was incredible, called Routine Pleasures. This French New Wave director moves to America and starts hanging out with the painter Manny Farber, and Farber’s ideas about art inspire him to make this strange but beautiful documentary about the local men’s club of train aficionados. It’s a model train club.

It’s an incredible film, and it’s partially about Manny Farber, so I started looking into this guy, and he’s cool.

His most famous essay is “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art” (1962). This is widely cited as the definition of his aesthetic philosophy. He says you have to avoid trying to make some grand masterpiece. You have to start where you are, start small, and become obsessed with something immediately at hand and unique to you.

You have to get so lost in something small that you begin to enter a unique private tunnel. This is the only way to get somewhere special. If your aspirations are too grandiose all you can do, at best, is become a kind of bricklayer for an overly rationalized structure that’s too big for you to live in.

a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn’t anywhere or for anything. A peculiar fact about termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art is that it goes always forward, eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.

The most inclusive description of the art is, that… termite-like, it feels its way through walls of particularization, with no sign that the artist has any object in mind other than eating away the immediate boundaries of his art, and turning these boundaries into conditions of the next achievement.”

He’s saying that great artists start with something authentic, intense, and personal, which is inevitably small and microscopic. But then they feel compelled to build big, expensive, weighty structures around it, which often do it a disservice.

I could not agree more, and it’s exactly what Deleuze and Guattari have in mind when they talk about rhizomatic becomings, being like grass, and so forth—to start in the middle. It’s the same intuition.

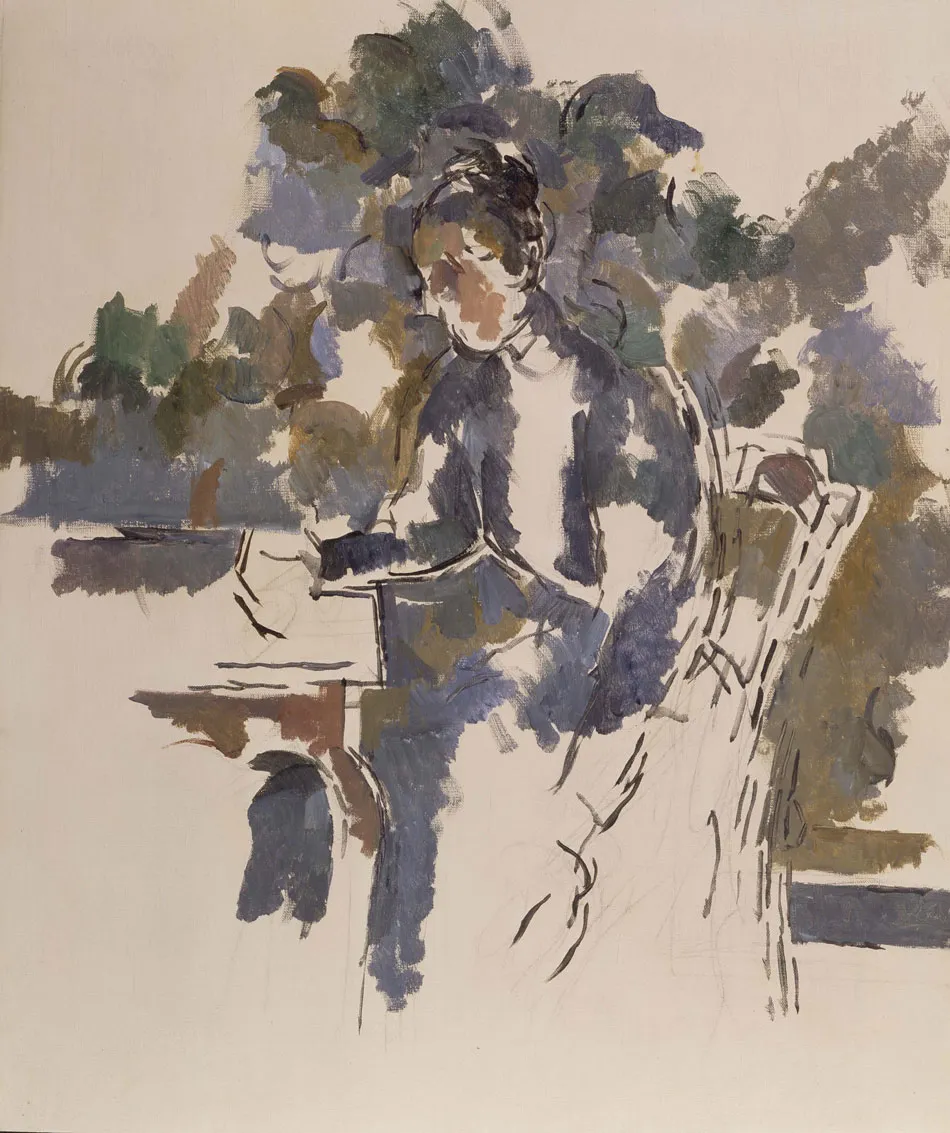

His first example is Cézanne, who seems to describe his own infatuation as a “small sensation” but then goes on to self-aggrandize. Farber thinks the work suffers from this aggrandizement, and he points to Cézanne’s unfinished watercolors, which he calls “terrifyingly honest,” and the occasional oil painting abandoned in the middle of things. His example is the pinkish portrait of his wife in the sunny patio.

The way to understand Farber’s painting is that he paints the small and specific things that interest him, but his real trick is simply to avoid doing anything else. Just study small things and paint them with all your force. Decline any additional aggrandizement. I love that, I think it’s very generalizable. He does the same in his writing, which is why it’s a little strange but extremely high-signal and stimulating.

Other examples he cites that exemplify the termite dimension are Laurel and Hardy and the film The Big Sleep. He says they “have no ambitions towards gilt culture.”

White Elephant Art

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Tony Richardson, 1962)

- Requiem for a Heavyweight (Mickey Rooney, Julie Harris et al., 1962)

- La Notte (Antonioni, 1961)

- A Taste of Honey (Tony Richardson, 1961)

- Shoot the Piano Player (Truffaut, 1960)

- Jules et Jim (Truffaut, 1962)

- The 400 Blows (Truffaut, 1959)

- Mischief Makers / Les Mistons (Truffaut, 1957)

- L’Avventura (Antonioni, 1960)

- Billy Budd (Ustinov, 1962)

- Two Weeks in Another Town (Minnelli, 1962)

Termite Art

- The Big Sleep (Hawks + Faulkner, 1946)

- Hog Wild (Laurel & Hardy, 1930)

- The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (John Wayne’s performance, 1962)

- The Iceman Cometh (Myron McCormack, Jason Robards et al., 1960)

- “the last few” detective novels (Ross Macdonald)

- Raymond Chandler letters (1981)

- William F. Buckley Jr.’s early TV debating style

- Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952)